This interview with Maryam Namazie is about refugee rights, criticism of religion, Islamism as a political movement, and the need for progressives to define a coherent political position beyond identity politics.

Maryam is a secularist and human rights activist, speaker for the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain, for the One Law for All – No Sharia Law campaign, for Fitnah, and for other campaigns and groups. She is also a Central Committee member for the Worker-Communist Party of Iran and co-hosts the YouTube & television program “Bread & Roses” (which, fitting with past interviewees, is under the CC-BY license).

You can follow Maryam on Twitter and on freethoughtblogs, and you can support Bread & Roses on Patreon.

Transcript

This transcript is edited for readability and length. A more literal transcription will be found in the subtitles, which will be posted later this month.

Maryam, what’s your passion?

I guess my passion is social justice. There is a really good saying by Mansoor Hekmat, an icon of the left in Iran, and he basically says people seek out the left because they want social justice, they want to change the world for the better. And I would say that’s my passion, just wanting to change things for the better and getting really frustrated at how unfair things are.

I’m lucky in the sense that I come from a background of Iranian politics where there is the possibility to be part of a wider, widespread movement that is for social justice and that doesn’t make excuses for either the Islamists or US-led militarism. Sometimes I think people feel like they have to take one side or the other, so in that sense it’s helped me to be able to channel my passion into real activism and one that I feel comfortable with and don’t feel like I’ve made compromises principle-wise.

You grew up in Iran and then you moved to the UK with your parents when you were a teenager, right?

Yeah, I was raised in Iran. I went first to India with my mum. She was going to put me in school there, and then go back to Iran, but then my father and my 3-year-old sister who was in Iran at that time, he told my mum not to come back, and so we were in India for two years and then we came to Britain for a year, but we weren’t allowed to stay in either country, so then we went to the US, and that’s where we managed to get residency. And I returned to Britain in 2000.

So when you left Iran as a young girl, what was your perception of what was going on at the time, and how did you process that?

I suppose the main issue for me for many years was refugee rights. It’s still a very important part of who I am, in the sense of just seeing your entire life break away and having to leave lots of family and friends behind, or even if you have family who have also had to flee, they fled to many different parts of the world. So you end up maybe not seeing your relatives for many years. My grandmother when she died, I never got to see her. My husband, his father just died quite recently, and he was unable to go back to the funeral.

So it’s a break in everything that you know. Oftentimes, when we hear about refugee issues, we hear about how people don’t want newcomers to come to their countries, but there is less about how difficult it is to actually leave everything you know behind and go to places where you may not feel welcome, you may not feel like you belong, and to try to rebuild your life.

It was easier for me given that I was young, but much more difficult for my parents, for people who are older and who will have to start all over again from the box after having done that years before.

[…]

It started with this whole refugee issue and then trying to look at why people have to flee, and then there is this link with the Iranian regime, an Islamic regime. I was raised a Muslim but it was never an issue in my life, so I wasn’t really forced to veil. I didn’t go to segregated schools. I was treated very much as anyone else in my family, I wasn’t treated differently because I was a girl.

So for me the first time religion in all its glory became evident was when it had political power. That’s why I think for me it’s very easy to make a distinction between people who are Muslims who might even believe in Islam (though I’m an atheist), who are just wonderful regular people, and the fact that they all have differences of opinion, they are not just one mass of robots trying to take over the world — versus the Islamist movement which is trying to take over the world, to some extent.

What we saw in the last one and half years is the largest movement of refugees in the world since the Second World War, and we’ve seen political responses to this all across the spectrum. What I have observed at least is, I’ve found sanity neither on the political left nor on the political right on a lot of these issues.

On the political right we see a lot of bigotry and we see a lot of hatred and a lot of: “Let’s close the borders, we cannot to afford to let people in, and we cannot afford to help. It is too much of a risk, it’s too much of a threat.” And there’s broad generalizations, as you say, like, “Everyone is against us. Everyone is trying to take over.”

And then on the political left it seems to me that there is often a kind of naiveté about Islam and Islamism and its intentions, while at the same time a more positive and responsible attitude towards [refugees], “Okay there are people who need our help and there is stuff that we can do.”

There is the Refugees Welcome movement. There are people who actually genuinely are trying to make this crisis something that we can overcome. But when it comes to the issues of Islam and Islamism, many of those same people are tending to turn a blind eye, and I have found that there is only a narrow niche of people who are concerned about both of these issues and tackle them head on.

As one example of this conflict, I want to go to something that happened when you were giving a talk about Islam and Islamism at Goldsmiths University in London in November 2015, and you were essentially giving a presentation, and you were interrupted rudely multiple times by members of the audience. After that both the feminist student society and the LGBTQ student society at the university actually defended the people who heckled you.

Yeah, can I go back to the refugee issue?

Absolutely.

Just to say a few words on that. The problem with both the right and the left perspective on this, and I say this as someone on the left, is that they homogenize groups and look at communities [as if] they all think the same way. So with the right for example, they are concerned about refugees coming in because they immediately equate all of these people with ISIS, with Islamism and terrorism.

And the reality is that a vast majority of these people are not linked to that movement in any way, they are just fleeing for their lives, they are fleeing because they want to save their life. Why they’re coming to Europe? Because, well, everybody wants to come to Europe, because people want to live freer, better lives, and it’s this dream of living a life without constraints. I think those who lived under the constraints of either a dictatorship like the Assad dictatorship or the Islamists understand this more than anybody else.

So this equation of Muslims — first of all, not all those refugees fleeing Syria are Muslims to begin with. Even if they are Muslims, they are not necessarily Islamists. A very small minority are.

They think that in order to defend refugees, they need to defend the Islamists.

With the left, too, what you see is that they look at refugees all the same — again, this homogenization — and because they too see Muslims and Islamists as quite similar with each other they also conflate these issues. You find that they think that in order to defend refugees, they need to defend the Islamists. What I am trying to promote is looking at people as human beings.

People are not more criminal because they are British citizens or American citizens, for example, even though U.S. militarism exists or imperialism exists. Or you have the KKK or the English Defence League, that doesn’t automatically mean everyone who is British or American [identifies with them], and it’s the same with Muslims and Islamists as well. Islamists are a very small minority.

It’s important to look at people as individuals. Of course there will be those who will commit crimes, and they might also have refugee status, in the same way that people will commit crimes and they have U.S. passports. Look a people as individuals. If they’ve committed a crime, prosecute them. But that doesn’t deny the fact that people have a right to protection, people have a right to refugee status, people have a right to live free from fear, from bombs, from the Islamists, and so on and so forth.

So it’s differentiating between helping someone, for example, to be free from living a life of domestic violence, that’s a right. To be free from a life of violence. The person who faces domestic violence may also have shoplifted, for example. You can’t then argue that we can’t defend victims of domestic violence because you have evidence of a few people who have shoplifted.

So I think not placing collective blame is hugely important, and I think that’s when we will start having a more human and principled view on those who are fleeing.

There are some people who argue that we should profile beliefs or profile ideology, to some extent. I have seen surveys of refugees where you find, okay, there is a small percentage of people who enter the countries, and they actually answer to the question “Do you think there is anything good about ISIS and what ISIS is trying to do?” with “Yes”. [See the 2014 Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies poll, for example.]

And there are people who say that anyone who would say such a thing in a survey is probably not the kind of person who should let into the country with open arms. What’s your take on that? Do you support any kind of ideological profiling or questioning, integration efforts that try to counter this kind of extremism in a meaningful way?

My point of view is look, you cannot base rights on people’s beliefs. You can’t say that you have the right to equality if you agree with women’s equality. “If you don’t agree that women are equal then, I am sorry, these universal laws of equality between men and women will not apply to you.” And take any other thing. “You cannot have fair wages if you don’t agree in labor trade union organizing rights, because it’s the trade unions that fought for you. You are a strikebreaker or you don’t support your local union activism, therefore you can’t have the same rights that have been fought for.“

You can’t give people rights that are theirs, that are inalienable, if we agree that rights are inalienable, based on what they think and based on whether you like how they think or not. I think that’s a very fundamental thing. If you need health care in America you might be someone who doesn’t support universal healthcare for everyone, but you still have the right to health care whether you think that it belongs to everyone or not.

And I think that’s one issue right there. The other is that just because people believe in a religion, doesn’t make them fundamentalists, in the Islamist sense, doesn’t make them fascists. You can have people who are very conservative, who are anti-gay rights, who are anti-gay marriage. You have that amongst Christians as well. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they are rampaging on the streets and attacking every gay person that they come across or discriminating against them.

So I think there is a difference between conservative views and beliefs, and action. I think if we look at Islamism in the way we look at the KKK and the way we look at Christian white supremacist groups or Hindu supremacist groups, it makes it easier to make a distinction between people who have religious beliefs who might be conservative versus the religious right wing, which is what we need to be concerned about because they’re the ones who are terrorizing people. They are the ones who are imposing sharia laws.

If you profile people on belief, you are going to get it very wrong.

The other thing too is that you can’t make a distinction on conservatism with one’s immigration status because you have people born and bred in the west who have pro-ISIS views and refugees who have risked their life defending secularism and what people would call “western values”, but they are really universal values.

That’s why if you profile people on belief, you are going to get it very wrong. Because it implies that people who are Muslim are Islamists, and that’s a very wrong assumption, because that’s not the case.

If it were the case you wouldn’t have mass migration from countries where Islamists rule, that’s number one. If you look at the countries where people are fleeing, the top ten refugee producing countries, they are countries where the Islamists are in power, a vast majority of them are.

Second of all, if the Islamists were really what people agreed with, well, they ISIS wouldn’t need to put banners up telling women how they need to dress. The Iranian regime would not impose segregation in football matches. Why would they need to do that if everybody agreed with the Islamist version of the world? So obviously they don’t. Which is why prisons in Iran, in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Saudi Arabia are full with freethinkers, including Muslims, who just don’t want to live according to what the Islamists say is the right way to live.

So I think that’s why profiling based on belief is wrong. I think behavioral profiling is what needs to be done. How do you find and seek out the Christian right who are bombing abortion clinics or trying to plan attacks? You don’t profile every white male, because the white men in America for example are not feeling discriminated against and targeted by the police. You don’t do that, but somehow, they do manage to know who these people are. In the same way we need to behaviorally profile the Islamists, rather than connecting them with Muslims.

If we [equate them with Muslims], what we also do is, we push more people towards the Islamist movement, because when you tell people that they are the only ones that represent you, whether it’s via policies of cultural relativism and multiculturalism, whether it’s via profiling, you do end up pushing more and more people to that movement, rather than rescuing them from that movement, and making very clear that they are not one and the same.

At some point that though does translate into governments doing things, right? At some point it translates into governments either deciding to let people in or keep people out, or it translates into governments surveilling people or not surveilling them, trying to keep them from harm or keep them from doing harm. In your view, what kinds of government interventions actually represent a reasonable defense against the Islamist threat, against Islamism as a political movement that, as you say, wants to take over the world?

I think that governments obviously have an important role to play. I may not like policies of governments, I may not like many laws that are unjust, but nonetheless when we are fighting for basic rights we are making demands upon the state, we are making demands upon the legal system, and a lot of laws and policies that are progressive, are things that were fought for by generations before us. It’s not something that has been handed over, it’s been fought for.

So I think within that same framework it’s important to pressure governments in order to do the right thing; they will never do it on their own. I think if we want to be safe — which is important, we all want to be safe; for every Paris or Brussels in the West there are similar terrorist attacks and impositions of sharia law on populations of the Middle East and North Africa.

There is a Paris or Brussels every day in Pakistan, in Afghanistan, Iraq and what have you. So this security issue is not just an issue for Europeans or for Americans. It’s an issue for Iranians and Afghans and Algerians and Moroccans.

And so one is to recognize that this is a global phenomenon and we need to work together. We have allies across borders and boundaries, and enemies that go across borders. You have people who are born and raised in Europe and the West, who are killing women and children and men in ISIS-held territories today. Some of them might even be white converts. So to see this as a global thing is hugely important.

And two, put pressure on governments not to deny civil rights, human rights, under the guise of defending security. If we are concerned about defending humanity, an important part of that defense is defending rights — whether human rights, civil rights that have been fought for and gained through a lot of hard work and sweat, tears and blood.

Rather than targeting citizens let’s say who are Muslims for example, rather than doing that, [we need] to compel governments to target the Islamists. If we look at the bombings in Paris or Brussels, I think a vast majority of those who’ve committed those crimes in London in 7/7 for example, they were already known to security agents. Why haven’t they been under closer surveillance so that they couldn’t carry out the attack? Why weren’t they stopped?

And many are being stopped. I know that in Britain for example every week one or two terrorist plots are being stopped. There is this acknowledgment even by security experts that we need to target the Islamists, for example. And many plots are being stopped, so at some level it is working. But to focus more on that, than on spending all this time on resources on targeting refugees; targeting Muslim communities — that’s not going to work.

Those are things of course that governments don’t want to look at because there is profit involved.

If you look at Islamism as a political movement, there are important aspects of that movement with very good relations with Western governments. Let’s say the Saudi regime. The Iranian regime. These are pillars of Islamism, yet they have got very close relationships with Western governments. The Saudi regime gets lots of money in military funding. I mean the police are even trained by the British government. Those are things of course that governments don’t want to look at because there is profit involved.

Nonetheless, if you want to have a comprehensive response to Islamism and not just its terrorist wings you need to look at these regimes. You also need to look at the political aspects of this movement. The problem is that a lot of Western governments feel that if they make concessions to the political arm of this movement, it will reduce terrorism, but it won’t. These two are intrinsically linked with each other. Any strength that the military wing has, it will strengthen the political wing and vice versa.

When you look at the political aspect of this movement, the imposition of sharia law, for example, in Britain we have sharia law courts. The British government refuses to address them. It says that it’s people exercising their right to religion. Our position, the position of groups that I work with along with other secular, even Muslim women’s groups is that this is a project of the Islamist movement.

As is gender segregation at universities, as is the women’s second class status in so-called Muslim communities, also the veil, the niqab, especially the burka, these are flags of the Islamist movement. If we don’t deal with this issue comprehensively we fail to address it, and that’s why we are not able to address it in the way that we must.

I think you brought up something very central just a minute ago which is the long history of support by the West for Islamist regimes. That history is well-documented and is also partially linked to just the West looking for allies against communism: “If we support the Saudis, the Saudis will be a power block here that will preserve capitalism, that will preserve our interests.”

And what’s seems to have happened in part is that those alliances have continued even though the strategic motivations that drove them in the first place have to some extent disappeared. So now there is this chaotic situation where the United States, and its foreign policy, doesn’t even know what to do with something like the YPG, the Kurdish liberation movement. “Are they our allies, who knows? Maybe they are, maybe they aren’t.”

And they continue this alliance with Saudi Arabia in the form of tens of billions of dollars, literally, of weapon sales in the last few years. And one thing that I wondered about as I saw the left and the right struggling with issues around Islam and Islamism in the last few years is, why is there not a broader consensus and a broader alliance among people of different political persuasions around this issue for example of Saudi Arabia?

It seems pretty clear that if you are Sam Harris, or if you are Richard Dawkins, or if you are Maryam Namazie, it doesn’t really matter, everyone should be able to agree that the United States and the UK shouldn’t be allied with a country that is the main sponsor of this very extreme ideology that Saudi Arabia has been promoting around the world for decades.

Is it fair to say that perhaps activists in the United States and Europe should put more emphasis there, and less emphasis on criticizing individual Muslims or criticizing even Islam as a religion?

I think there is a couple of things here that you raised. One is the history of the West’s support of Islamism. So even in Iran for example, the 1979 revolution was not an Islamic revolution. It was a left-leaning one, and Western Powers met at the Guadeloupe Conference to decide that they preferred an Islamic state to a left leaning one and that’s when we see the support for Khomeini who was someone who no one knew, really.

And we know what’s happened in Iran since then, so as you say it was creating a green belt around the Soviet Union at the time. I don’t think though that strategically it’s no longer an issue for Western Powers. I think whilst the Cold War has ended, religion in general is a very useful tool for governments to control and manage the population at large. It’s continued to be useful tool, including in societies where religion is no longer even relevant, really.

You still have such a strong role that religion plays in Britain for example even though it is such a secularized society. In Ireland for example you see people voting for the first referendum in defense of gay marriage, in a country where it seems so conservative and religious, that’s the impression that’s given because of the role that the Catholic Church still plays in that society and in the state. So I think it’s very useful.

Also, if you look at Western government policies now with multiculturalism and cultural relativism, the Islamist movement is very useful in managing minorities on behalf of the state. So we are seeing a situation where the so-called Muslim community has their own schools, they have got their own services even, the sort of faith-based services, as if we don’t all bleed the same. We don’t need to go to a secular hospital any more, we need faith-based services because somehow we are so different, even our biology is different, we need separate services to address our needs.

And also of course faith-based courts. In the sort of climate where there are austerity measures, cuts in legal aid, for example. Well, privatizing and outsourcing justice to Islamist groups has been very useful Wor western government policies. And so I think in a sense everything is so intertwined with each other, it’s not just the Saudi regime. It’s about so many fundamental policies, social policies, political policies in Europe as well, in managing so-called minority communities.

But it’s also very much part of Western government foreign policy. So in Iraq, dividing societies based on ethnicity and religion, the Iraqization of the world really, it is a very good way of managing. Or [so] they think at least — it’s obviously been a disaster in Europe, it’s been a disaster across the world.

So I think that’s one of the reasons why it’s not so easy to separate all of these things. And again with the Saudi regime, the problem I have with many people on the left is that they’re happy to criticize the Saudi regime because it’s got close relationships with the West but they are in bed with the Iranian regime, they are in bed with Hamas and Hezbollah, and in that sense if you don’t deal with a movement comprehensively, you are not going to be able to address it, because the Saudi regime is only one part of it.

The other thing with the Saudi regime is that it has been untouchable for so long because it’s so closed and we haven’t been able to see the resistance and protest. They’ve been able to make it seem as if this is what Saudi society wants. Now though there are cracks, and a lot of it has to do with for example the campaign for the release of Saudi freethinker Raif Badawi. His wife’s campaign, Ensaf Haidar’s campaign for his defense has cracked open the façade of it being untouchable.

I think with that campaign, we are seeing the sort of momentous movement of groups and organizations who are coalescing together as many of us have in defense of Raif and against the Saudi regime, and I think that’s something that we are going to see more and more of.

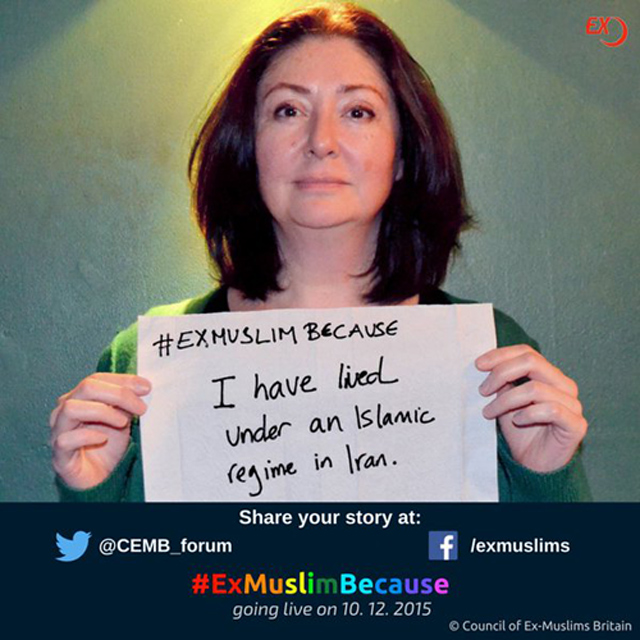

From the #ExMuslimBecause campaign.

I take your criticism of the left as being often supportive of Hamas and Hezbollah and groups like that as very valid. At the same time one criticism by the left of people in the anti-Islamism movement and groups that are against sharia law and so on is often being framed as, we should not “punch down”. We should always “punch up”.

And the framing on the left is often to say, if you are criticizing Islam as a religion, as a belief system of people let’s say in the suburbs of France, then we are effectively punching down, we are not punching up to people who have power. We are punching down to people who don’t have power.

Would it be fair to say that perhaps people who hold that belief and people who are concerned about Islamism can meet and find common ground around this issue of political connections to regimes, whether it’s Saudi Arabia or whether it’s Hezbollah, and jointly take collective action against Islamism that is being promoted, and focus more energy there? Focus more attention there and focus less attention on Islam as a belief system and how ridiculous different kinds of religions may or may not be.

Those are very legitimate points. First for, me it raises the question, why do you think you are punching down? Do you know what I mean? Why, and I think it goes back to this fundamental belief that Muslims are the same as the Islamists. Therefore, if you want to defend Muslims, you need to defend Hamas and Hezbollah. So my point is that Hamas and Hezbollah are oppressive forces in their societies, as is the Iranian regime, as is Assad’s regime, which many on “Stop the War Coalition” for example will defend, though they don’t defend the Saudi regime. They are exactly the same as the Saudi government. They are power sources. They are a form of imperialism in the Middle East and North Africa.

If you look at pictures of women in Iran, in Afghanistan 40 years ago, they are unrecognizable.

If you look at many of our societies 30, 40 years ago, they have completely changed as a result of the Islamization of those societies. I am not talking about Europe. Music has been banned in Mali. The traditional dress of many African Muslim women has completely been changed, it’s been de-Africanized and it has been Islamized. There are many, many examples of this across the world. You just look at any society and you will see it. If you look at pictures of women in Iran, in Afghanistan 40 years ago, they are unrecognizable. Today you would not believe that they are women from the same society. It looks like we have gone backwards rather than forwards.

So in that sense, why do you think it’s punching down? While this is often seen as a progressive position, there is a racism there. There is an underlying racism that one, those of us who come from minority backgrounds, that we can only ever be fascists, we can never ever be revolutionaries, and also that we’re different from you. You can take criticism of religion. You can take criticism of your far right movements.

But if we from within, even those of us from those backgrounds do it, we have taken on the colonialist mindset. We are promoting a westernized neo-colonial outlook. We are coconuts. We are native informants. So there is this racism in that position that we cannot have freethinkers and revolutionaries, only you can. Only you have the toleration to laugh at your religion and to poke fun at it and to be anti-clerical.

We have to live within the confines of Islam and Islamist rules and that’s all that we deserve. So this cultural relativist attitude is so dehumanizing to begin with and it fails to see that just like you, we have dissenters amongst us. Just like you we also want to live freely, live without constraints, particularly religion constraints.

The other problem is that a lot of these groups see Hamas and Hezbollah or the Iranian regime as the “resistance”, because they have these blindfolds where the only concern they have is US militarism and imperialism, and anything that seems to be opposed to this is their ally and their friend. And my point is, well, you can be anti-imperialism and you can also be anti-Islamism, and rather than siding with one of the two sides that are in my opinion two sides of the same coin — side with the working class. The progressive social movements, political movements that are standing up to both, why can’t you do that?

People will often accuse people even like myself of feeding into racism against Muslims because of my criticism of Islam and Islamism. And what I would say is, look, I don’t blame so many on the left, like the Goldsmiths Feminist Society or the LGBTQ+ Society, which sided with the Islamists, against me, I don’t blame you for my death threats. Please don’t blame me for racism. Because I am a campaigner against racism and I fought it tooth to nail as I have fought the Islamists.

Blame the fascists and the racists for racism. Blame the Islamists as I blame the Islamists for the death threats. I don’t blame everyone who appeases them. And that is a long list of people on the left who should be siding with me. So I think, put blame where it’s due. Hold those movements that are carrying out racist attacks, that are promoting racism, that are promoting terrorism, hold them to account and stand with those of us who are against both racism as well as Islamism.

I want to draw the connection here with what I would describe as identity politics in the left today. You said earlier one of the problems with this argument about punching down is that — they are not all the same! And in fact when you do that, when you homogenize like that, you essentially create these isolated groups where you say, okay, if there is abuse happening within these groups then we don’t really care about it because that’s “just their culture” or that’s “just their religion” and we are not free to criticize it. We are not free to call it out. We are not free to name it in the same way as we would in our societies, in our culture.

And that seems to be an outcome of this view of identity politics where you group people by their religious identity or by other forms of identity. And so I want to draw the connection to the Goldsmiths incident. And what happened there is that you were shut down — or rather I should say people attempted to shut you down, they disrupted and heckled you and you carried on bravely as they did so. And they even tried to shut down the projector while you were speaking and pulled the plug while you were showing the slide.

And it was kind of baffling for a lot of people, I think progressives on the left, people on the right, when these responses followed where people at Goldsmiths University, students at university said, we actually side with the Islamic society on this one and we hope that the university will not invite a speaker like that again, effectively.

What was your immediate response to that, you reaction to that, and how do you empathize with that point of view? What’s your reading of the situation? How do people come to this conclusion that it’s okay to heckle a speaker, it’s okay to attack a speaker in this manner and then side in act with the hecklers? What ideology drives that?

When that happened, you know, I don’t expect much from the Islamists or the far right. I mean, what they did didn’t surprise me. I am glad it was videotaped because I know what would have happened. I would have ended up being vilified for it because before the video went up, the Islamic society did say that I basically violated their safe space and that I was screaming at them and that I discriminated against them and so on and so forth.

Had it not been videotaped, I would have gotten the bad end of that deal because there is this assumption — that’s the mainstream assumption — that they would be right and I would be wrong. And it’s interesting because all of this discussion is framed within the context of minority rights, but I am a minority within a minority.

I am a woman versus men, “brothers”, the ISOC brothers who were doing this. Also I’m an older woman, I am the age of their moms most probably. It seems none of that is relevant, which is interesting when you look at it, and the only thing that seems to matter is when you are looking at this power imbalance which they talk about so much is that they seem to be the representatives of power imbalance.

But when I heard about the solidarity message of the Goldsmiths LGBTQ+ society and the feminist society, I did scream at the top of my lungs at my computer.

And it goes back to this identity politics doesn’t it? Basically what you are saying is that our fascists are the ones who need to be protected against those of us who are fighting fascism. So when they behaved that way I wasn’t surprised because I have dealt this with movement for many years now, around 30 years where in various ways I’ve been up against this movement. So for me their behavior wasn’t surprising.

But when I heard about the solidarity message of the Goldsmiths LGBTQ+ society and the feminist society, I did scream at the top of my lungs at my computer. Because it does feel so hurtful, do you know what I mean? I can’t explain it. I am not surprised and I know it’s business as usual but it is still does feel very, very painful. Because they are the ones who I would expect should side with me, and that’s why it makes it more painful. So it’s kind of feeling like you are being stabbed in the back and in front by people who should be standing side by side with you.

And so I know it happens all the time but I still find it really hard to get used to.

Why does it happen?

It happens again, I think, because of identity politics and the homogenization of the Muslim identity. Those who are most fundamentalist, most conservative, most medieval are the authentic Muslims and therefore, if you are a burka-clad woman waving the ISIS flag that is the authentic Muslim woman, and if I or other Muslims are standing next to her having a discussion, these feminists will side with her.

It is sort of like the authentic Muslim is always a reactionary. And I do say this partly tongue in cheek but partly I mean it when I say that I feel offended on behalf of Muslims that there is such a poor view of Muslims. Imagine if everyone thought every American was like Donald Trump or Dick Cheney, or that the KKK represented all Americans and that in order to defend Americans we must defend the KKK, because it’s your culture to be racist and you can’t handle any more. Segregation is part of your history, and why would anyone defend black and white people fighting for de-segregation and join the civil rights movement? It’s a violation of your cultural rights.

That sort of thing is what’s being done not just in minority communities here and the West but across the globe. We have people being slaughtered, an entire generation for example slaughtered in Iran by the Islamic regime of Iran, and you have Stop the War Coalition organizers kicking out political activists from Iran who have signs condemning the Iranian regime for its executions. I mean sometimes it is so bizarre.

What happened to real human solidarity that went beyond the sort of narrow identity politics, one which went beyond borders, beyond color, beyond sex, beyond nationality, to linking up with progressive social and political movements, when you can only see identities, and the authentic identity is usually the one with power?

Because who decides what the authentic identity is? It’s those in power, it’s the mullahs, it’s the Islamic organizations, it’s Islamic states. And so basically this left, which gives the impression that it’s for the poor and the oppressed and it’s trying to help those who are being punched down, in fact what it’s doing it’s allying with those in power. Which is so ironic when you think about it, and so heartbreaking as well.

One of the other policies that get invoked in those contexts are the safe space policies, and I think it was also mentioned in this case, this notion that universities want to provide environments that are free of discrimination, free of harassment.

And at the heart seems to be this idea that we want to protect people from very real discrimination, very real hatred that people have encountered on campus, students have encountered in schools, bullying and so on.

There seems to be well intentioned desire to protect people from harm at the root of these safe space policies. Do you think that there is a good idea at the heart of them that’s worth protecting and changing, or do you think it’s just a completely wrongheaded idea to begin with?

Look, safe spaces are very important spaces. The fact of the matter is that as someone who is ex-Muslim, I organize safe spaces for ex-Muslims to be able to take off their veil because some of them are still pretending to be veiled, who are still going to the mosque, where they can come and talk with each other about issues that they face — ostracization, whether it is intimidation or just how to break the news to their family without losing their loved ones.

Do you think racists can tell the difference between Muslim, ex-Muslim, migrant citizen?

So I think safe spaces are important. We all have our own version of safe spaces, don’t we, where we go to feel completely comfortable and not under attack, and I completely understand particularly those who face discrimination and racism in the wider society. And that includes people like me.

Do you think racists can tell the difference between Muslim, ex-Muslim, migrant citizen? If you are brown, you’re brown. If you have a different accent, if you got black hair, it’s obvious. I see it in how sometimes my child is treated who was born and raised in this country. He is 10 now and he will ask me, why are they looking at me this way, or why did they say that, and it’s really hard to explain, wanting to give him this feeling that he is a citizen that belongs.

So these are things that we all grapple with. The sort of discrimination and racism. But the fact of the matter is that if you are going to protect minorities at the expense of other rights, it’s going down the wrong route, because first of all minorities need free expression more than anybody else. People who face discrimination, people who face racism.

Because free expression allows you to speak up and to criticize and to challenge. Actually free expression is the right for people who are powerless vis-à-vis those in power, and therefore minorities are some of the more vulnerable with the least power and influence in society. So they need that free expression the most, and when you start limiting it even for those who you think are disgusting and vile, you create the framework where limits are possible, and it’s those who have least power that face it the most.

Look, creating a safe space for yourself is very different from them saying that society at large or universities at large are meant to be safe spaces, because it’s impossible in the sense that universities are places where you are actually going to hear things that might be very unsafe idea-wise, which challenges your very being to the core and might even persuade you to think differently. So I think we need to make a distinction between those.

This sort of defense of minorities by ensuring that they don’t hear any criticism of their views has reached a point where criticism of an idea like Islam is seen to be the same as discrimination against, and attacking and even violence against, inciting violence against a minority community, and this is absurd! This sort of equation of speech with real physical harm is absurd.

I think to challenge that we need to speak as loudly and as forcefully as possible, and in order to start challenging these sorts of limits, to break the taboos that come with it, and I think in a sense this is the greatest service you can do for minorities if you are so concerned about them.

What’s interesting also to me is that your talk for example was obviously completely optional event, right. Nobody was forced to show up, nobody was told, “You all must now be subjected to this presentation on Islam and Islamism.”

It’s a very different situation from a student walking on campus and hearing let’s say a racially charged slur being thrown at them. You are presenting to a willing audience who all essentially chose to be there and said, this is something that interests me, and yet members of that same audience then said, no actually we would like to stop you from speaking.

So the safe space doesn’t really seem to apply in that same way to that type of setting. It’s a very different kind of setting than saying we want our campus to be discrimination-free, for example.

But also just to go over that event, what happened was, they had initially asked the Atheist Society to cancel my talk altogether, and when we went ahead as planned, they basically came to cancel the talk.

So in fact if any violation of safe space has taken place it’s by the Islamic Society brothers (not the sisters, because they were there, we had a conversation, we didn’t agree, but it was fine). It included actually threatening. They issued death threats against one of the audience members, by putting a gun to their head.

You can’t see the President of the ISOC doing that, but you see the person who he did it to telling the security guard, and you also see a Libyan women’s rights campaigner, Magdulien Abaida who was there. She puts her hand down in her face and she starts crying because it upset her so much. Now she is someone who was abducted by the Islamists in Libya for three days and threatened with death. So when she saw the guy do this, she just broke down at the meeting.

Another thing that’s on the video is when he was finally taken out by the security guard, he went to one of my colleagues and went “boom”. All of that seems to be okay, and again what’s interesting is this idea that they can actually threaten people because they are “authentic Muslims”.

Which is really saying that Muslims are violent, they are incapable of hearing anything that they disagree with, which again let me reiterate is so fundamentally racist. That’s okay, and it’s my being there that’s a problem. And what I found really outrageous after this whole incident was, the student union contacted me via six emails, left countless phone messages, not to apologize for what happened, not to say, well, “we are sorry as the external speaker that you have to face this”, but “please remove that video because it is violating the privacy of our students”.

They also made countless complaints to YouTube and YouTube basically said that because no one is named, there are no personal details of anyone in the audience, that they are not going to force us to remove it. What I told the university was, there is an investigation supposedly taking place, don’t you think it’s good to have the evidence available? But you want to take it down.

The professor had said that you can’t criticize FGM because it would then be promoting a white colonialist perspective …

I just met a student from Goldsmiths, actually the same women who filmed this, she is a student there. She is a Nigerian women’s rights campaigner and an artist, and she wrote a blog recently, her name is Sarah Peace. She wrote a blog about a class that she was in where the professor said that you cannot criticize FGM (Female Genital Mutilation).

[…]

The professor had said that you can’t criticize FGM because it would then be promoting a white colonialist perspective and it would be denigrating minority populations. Now Sarah, who is a Nigerian herself, was outraged at this, saying that FGM is something that many African women are fighting against, many women across the globe are fighting against, how can it be Western imperialism and colonialism to do that? She wrote a blog post about this. She didn’t name the professor but she wrote about it. Now I met her just a few days ago and she told me that Goldsmiths is thinking of putting her up for disciplinary charges because of her blog post.

Now none of the ISOC members of Goldsmiths who came and threatened audience members, who came and disrupted things, none of them were put under disciplinary charges, and Goldsmiths never said that they embarrassed the university. But they have told her that because she has embarrassed the university that they are looking into it.

And again, it’s the authentic Islamist, which is our fascist, can do whatever the hell they want, they can come on campus day in and day out. Impose gender segregation, as they did at LSE for example at a dinner, and you have the head of the student union who is a white woman “feminist” going and saying how wonderful it was. Well, gender segregation is like racial segregation but she has no problem as long as the ISOC is doing it.

And on and on and on, and then you have someone like me and suddenly I am “controversial” and I’m “inflammatory” and I’m “inciting violence and discrimination” and then you can see how alone sometimes we dissenters feel, especially when it’s people who should be on our side doing it.

Did they ever reach out to you, the feminist society, or did you talk to them after this happened, or the LGBT society?

No, they never did talk to me. I know that there were some differences within the group. I did hear that that there were some who were not happy at the position that they took but they never retracted their statements, even though Mohammed Patel who was the President of the ISOC as a result of scrutiny on him, a lot of homophobic tweets came up, and he was forced to resign.

“Forced to resign”, they are going to bring another homophobic, apostate-phobic, human-phobic President and they will carry on with their business as usual. But what is interesting is that because of his homophobic tweets he was forced to resign, but he can issue threats against apostates, but that’s “part of his culture”, isn’t it. We should just take it and respect it and of course it’s our fault that we get death threats. That’s the other thing, blaming the victim, there is a constant blaming of victims including by many on the left.

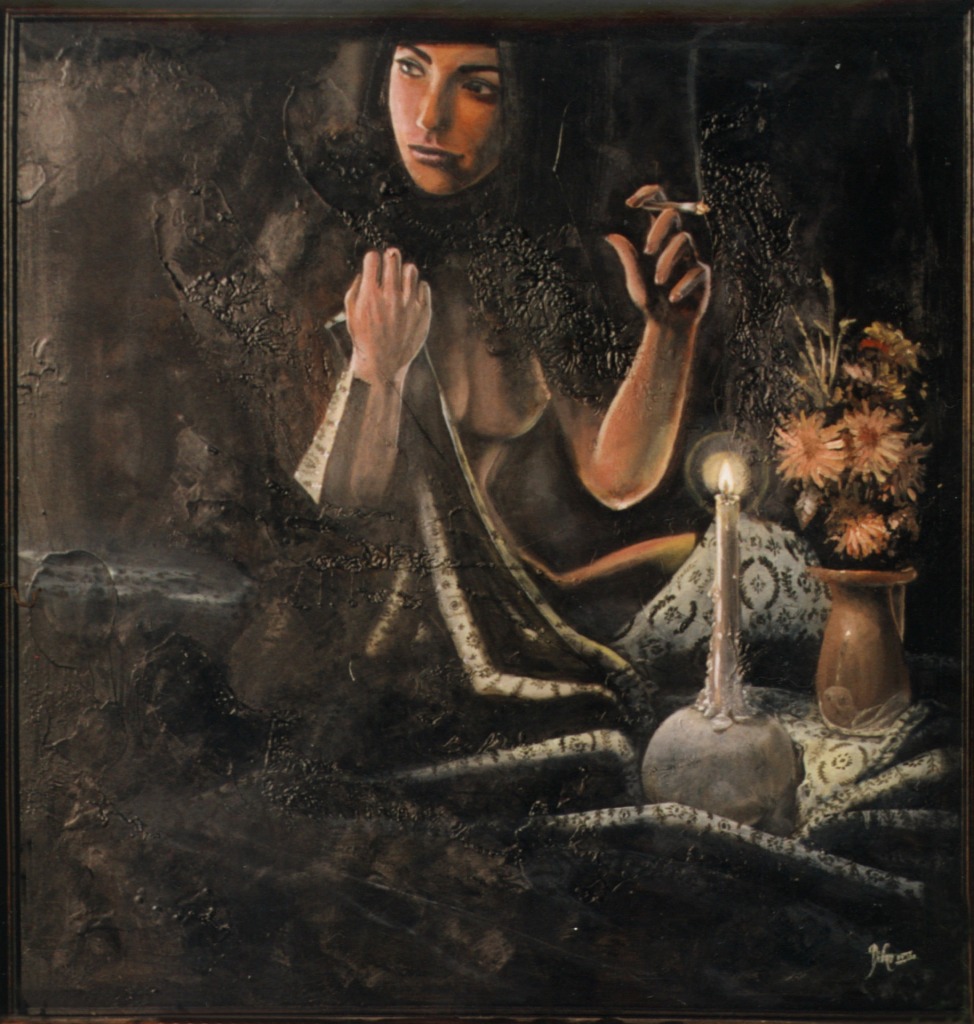

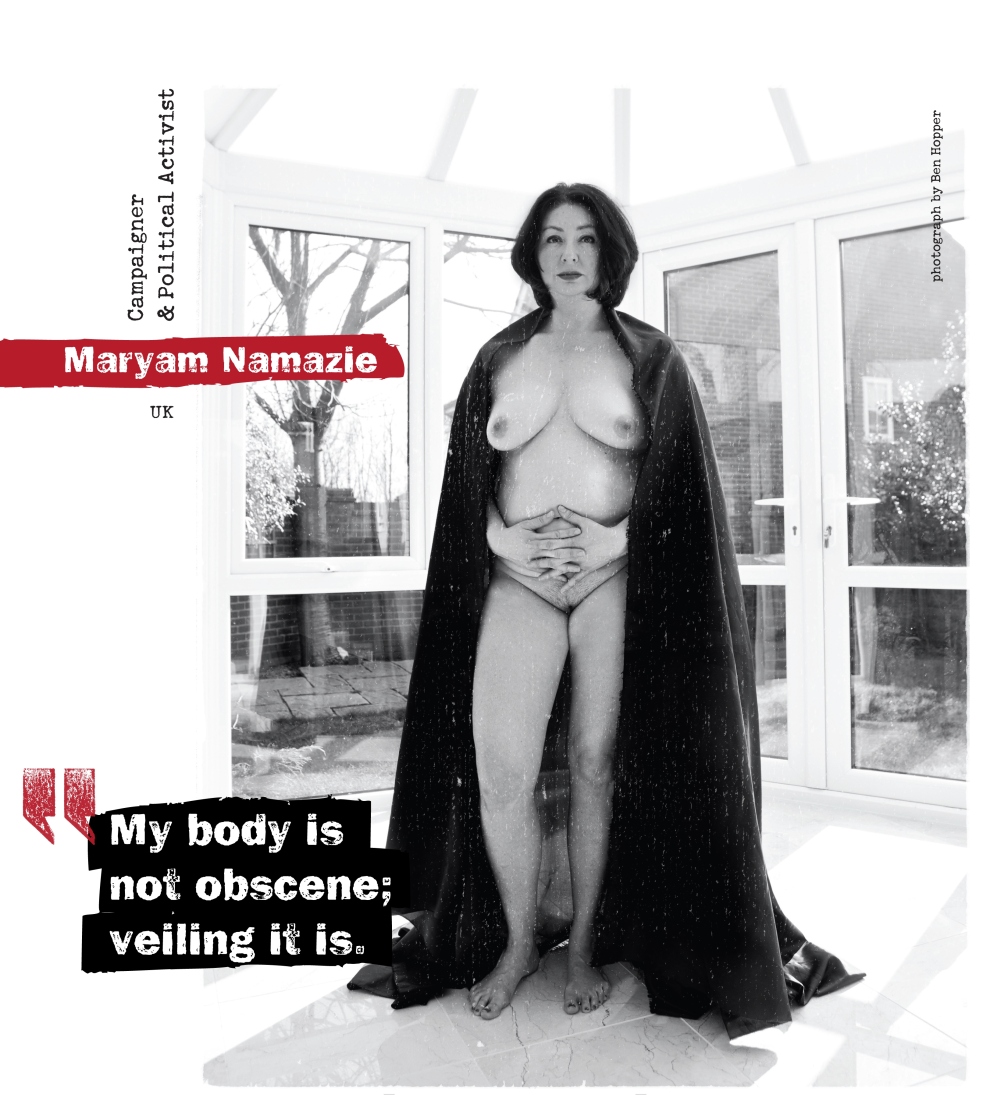

From the 2012-2013 Nude Photo Revolutionary Calendar (PDF). Photograph by Ben Hopper

Before we wrap up, I want to change a little bit to a different subject which is how are you as an activist on these controversial issues get attention, and get visibility and get people to talk about things that matter.

And one of the things you have done often is to provoke, to provoke within some of your presentations, to show things that you think are relevant for people to see and for people to engage with, but you have also provoked in protests and in other ways.

I want to talk a little bit about provocation and about how you’ve used nudity as a form of protest. What is the value of transgression, what is the value of provocation in bringing attention to these issues in your mind?

People will say that I am unnecessarily provocative and I think it’s not unnecessary. If you look at this movement that I am opposing, it decapitates people, it flogs people for writing a blog, it actually still digs ditches and stones people to death in the 21st century.

So if you think that my coming out and creating a movement saying we are ex-Muslims and apostates, we have a right to live irrespective of what the Islamists say and we are going to do it in public until blasphemy laws are abolished — if you think my saying that because my body is so despised and Islamists are so busy trying to erase and disappear women from the public space by veiling them, by silencing them, if you think nude protest is an “unnecessary provocation”, you don’t get what we are up against and you’re too busy criticizing those of us who are trying to resist, rather than criticizing the real fascists, those who are denying rights across the board.

So I think again this whole idea of provocation, as myself being seen as provocative, goes back to buying into the Islamist narrative, accepting the Islamist narrative as the norm. If anyone doesn’t do as they say — because that’s what you are telling me, do as they say, dress modestly and no one will bother you. Stop saying you are an apostate, and no one will bother you.

You could be at the marketplace at the wrong time and that’s it. That’s the end of your life.

Look, we know that they are provoked by anything. Forget about protest, they don’t like it if you fall in love with the wrong person. They don’t like it if you are “improperly” veiled. You are still veiled because it’s compulsory in Iran but they don’t like that it’s not exactly the way they tell you to veil. They don’t like it if you wear bright colors, they don’t like it if you sing, they don’t like it if you’re gay, they don’t like it if you breathe, if you dance.

So in that sense everything, every 21st century living act of humanity is an offense to them, is a provocation to them. You don’t need to draw cartoon of Muhammad to provoke them. You can just be sitting at a café in Brussels and you get it, you could be in the wrong mosque in Iraq and you will get it. You could be at the marketplace at the wrong time and that’s it. That’s the end of your life.

I want people to stop focusing so much on what we do and focus on them. I will do anything and everything I can that is non-violent and that can challenge their narrative, their status quo, challenge them.

I have responsibility to do it for the people who I’ve left behind, for the people who live in much more restrictive societies than I do and who can’t necessarily do what I do. But of course there was a women in Iran who did a topless protest recently, and she said, “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave”. In Iran, with a Iranian landmark behind her!

So this is something that goes beyond borders and boundaries. There are lots of people in Iran who support nude protest. There are lots of white feminists who oppose it. It goes beyond race, it goes beyond nationality, it is about politics, radical, progressive politics that aims to change the status quo and the Islamist narrative. Unfortunately, so much on the left have become so regressive that they can’t see progressive politics even if bites them on the ass, and they think it’s problematic.

It goes back to this whole idea of free expression being a cornerstone of all things. I have only limited ways in which I can speak. I can speak, I can use my body as a form of protest, I can organize various movements, try to get allies across various borders and boundaries. Whatever way I can, I can write, I can have a TV program (that’s incidentally broadcast in Iran via satellite dishes).

So these are the things I can do. Don’t tell me how I should do it, don’t put limits on my activism. That’s what free expression means. You do it your way and I will do it mine. And I will do it my way and as far as I can, I will push as much as I possibly can until the day that I die, because I have a responsibility to do that.

What is the proudest achievement in that form of activism for yourself, what is the thing that you look back to and you say this really worked well, or this really brought a message across in a way that it couldn’t have been brought across otherwise?

I have lots of high points in the sense of successful campaigns, whether it’s preventing the deportation of a group of Iranians for example from the Netherlands, having people call me from the Iranian Turkish border saying that they have been saved as a result of the work that I have done, with others of course in the Federation of Iranian refugees. I have lots of successes of that nature. Even if it’s just one person, it is that one person that has a different life as a result of work that’s been done on their behalf.

There are also human rights cases, for example, stopping the stoning of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani. I mean that is such a highlight for me, the fact that her [son] contacted one of my colleagues Mina Ahadi, and said my mom is going to be stoned any day now. And we had this wonderful international campaign where we had actions in hundred cities across the world and she is now today a free woman.

And there are many instances of that sort. And of course the Council of Ex-Muslims. I remember when it was started, we couldn’t find 25 names and faces of people who were willing to say, “We have left Islam”, and a lot of them, if you look at the initial photos, are Iranian political opposition which is used to criticizing Islam and Iranian regime.

And today it’s become a mass movement really where there are ex-Muslim groups in many cities across the world thanks also to of course social media and also the work of people like Richard Dawkins and their support of this movement.

The fact that now wherever I go there are people saying, “I am ex-Muslim”, it’s because of the Council of Ex-Muslims that I was able to do that. And there is this great thing that we started, which one of my colleague started, Rayhana Sultan, she’s a Bangladeshi atheist, and she came up with this idea of #ExMuslimBecause, and it’s a hashtag where someone will say, “#ExMuslimBecause I am a woman”, “#ExMuslimBecause of bacon”. Rayhana’s was, “#ExMuslimBecause there is no 72 virgins for me.”

There were more than 120,000 tweets from 65 different countries …

So it was both funny but heartwarming as well. I just met a few days ago the woman who said hers was the one where her face was hidden and she said “#ExMuslimBecause my father was an imam and he forcibly married me as a child”. So also very heartbreaking ones, and people who said it was the first time that they ever came out as an ex-Muslim. There were more than 120,000 tweets from 65 different countries so again that is something where you feel, you are having an impact, it makes a difference, and that just makes you want to do more.

The thing that I guess personally was the most difficult thing for me was of course nude protest, because I find the fact that you are coming from societies where women are told to cover up, where your body is seen to be the source of chaos and fitnah. There is this hatred of your own body in a sense, and this feeling of shame, and to be honest, I can’t say I have completely gotten over it, even though I am known now as somewhat a topless activist or nude activist.

The first thing I did was this calendar for Aliaa Magda Elmahdy. She is an Egyptian blogger, and she posted a photo of herself and she said, “Put on trial the artists’ models who posed nude for art schools until the early 70s, hide the art books and destroy the nude statues of antiquity. Then undress and stand before a mirror and burn your bodies that you despise to forever rid yourselves of your sexual hangups before you direct your humiliation and chauvinism and dare to deny me my freedom of expression.”

She did this in Egypt. She was also kidnapped by the Islamists. She now lives in Sweden as an asylum seeker, as a refugee. So I did a calendar which is still available on the website that I just want to show you. I did my photo and mine was saying, “my body is not obscene, veiling it is,” and it was the most difficult thing I ever did. It took a while for me to manage to get my photo because it was so difficult.

And after that I did other actions in public. One was taking the Allah out of the the Iranian regime’s flag and putting something much more worthy in his place — I wrapped it around my waist. And that was in front of the Louvre in paris with Aliaa Magda Elmahdy and also Amina Sboui, who is a Tunisian topless activist.

So I guess personally that was the most difficult for me. I always still say, put me in a room with 20 Islamists, I’ll be fine, but ask me to do nude protest and it’s so much more difficult because there are so many other things involved.

It’s not seen to be as heroic, there is this shame attached to it, and there are people who still won’t work with me because, “This is just going too far, you just go too far”. And I think history is made by people who go too far and who do things that are vilified, that are looked down upon, that are seen to be rocking the boat too much.

So I think, no I am not going too far, the Islamists go too far, and we are just trying to defend humanity against them, basically.

Well thank you, Maryam, for rocking the boat and for sharing your passion with us today. I would encourage folks also to check out Maryam’s YouTube channel, which you can follow regularly for information about the work Maryam is doing on many of these issues, and also to follow Maryam on social media and to follow her activism and to get involved if this show spoke to you. Look at the hashtags that were mentioned. Look at the links, there is lots more here to read about. Thank you again Maryam for being with us today.

Thank you for giving me the time to explain my thoughts and views, it’s brilliant, thanks. Good luck with the rest of your program as well.